On a rare sunny day on the last Wednesday of October, PHBS-UK has the distinct pleasure of welcoming Professor Matthew McCartney to share with our staff and students his research on the economic development and the railway renaissance in Africa. Prof McCartney is currently the senior researcher at Charter Cities Institute – a non-profit thinktank that is dedicated to creating the ecosystem for new cities who are granted special jurisdiction to create a new governance system, i.e., charter cities. Before joining CCI, Prof McCartney spent twenty years as an academic at the School of African and Oriental Studies (SOAS), University of London (2000-2011) and at the University of Oxford (2011-21). His academic experiences extend beyond the UK where he has been a visiting Professor at universities in China, Pakistan, India, Japan, South, Korea, Poland, and Belgium. Apart from his academic endeavours, Prof McCartney has also worked for the World Bank, USAID, EU, and UNDP in Botswana, Georgia, Bangladesh, Azerbaijan, Egypt, Jordan, Bosnia, and Zambia. With such an impressive background and experience, and this is just barely scratching the surface of his accomplishments, it is a definite honour to have Prof McCartney here at the Campus with us to share his experiences and expertise.

In his seminar, Prof McCartney shared with the audience the vision – the Dragon’s Dream - of the African Union: to have an interconnected Africa with an integrated African economy, a free trade bloc, and free movement of people in Africa. A vision to be made possible by high-speed railways. How is this vision going to be realised? Does one run stimulations, i.e., CGE? Would that be enough for an undertaking as massive as linking the entire African continent? All good questions and these questions from the crux of Prof McCartney’s research. With a project so large, Prof McCartney highlighted that it would not be possible to model the complexity of this undertaking with CGE. Railways have a profound impact on economy so all the equations for CGE might be out of date. So how does one go about such a momentous task? One of the ways, as Prof McCartney suggests, is to draw lessons – both regional and thematic - from history.

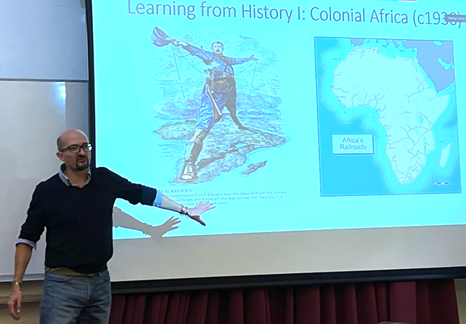

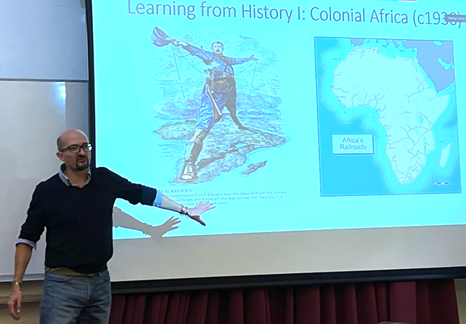

One can learn much through looking at the different railway constructions throughout history and draw lessons from the various projects and see if these lessons could apply to contemporary Africa. Prof McCartney raised 4 railway planning and construction lessons: Colonial Africa (1930s), the Trans-Siberian Railway (1904), the US Transcontinental Railway (1869), and the Asian Sub-continent (1909). From Colonial Africa in the 1930s, we can see that the railway system put forth was one that precipitated disintegration due to the fragmented colonial government. However, when you compare that to the Trans-Siberian Railway, you see a different story where the railway liked up the continent and transformed Russia into a single nation, i.e., it promoted integration. The key to success here, as Prof McCartney put it, is to have an integrated government who can see the big picture and plan for the success of the whole land mass.

What about lessons in economical development? Prof McCartney drew lessons from the US continental railway (1869), whose development saw national integration, opened up the US land mass to agriculture and mass migration. After the creation of the railway, the US became the main exporter in agriculture. The UK benefitted from the huge export of agriculture, the people do not have to work in farms which resulted in the age of industrialisation in the UK. However, not everyone benefited from the US boom. Europe entered depression due to the cheap agricultural exports. The lesson learnt here is that the impact of railways is global.

Similarly, while analysing the railway construction in the Asian sub-continent (1909), Prof McCartney presented a very different picture of India’s railways under British colonial rule (cf. the colonial rule in Africa). Railways linked landlocked India with coastal areas. However, the British motivation in India was very different; their focus then military not economy. The British quickly realised that they could move a modern military very quickly around urban India. However, the lessons learnt are that the railways did not promote industrialisation in India; the British had a rule that everything used to construct the railway must be from Britain. As such, Britain benefitted economically, not India.

Now, one might ask how would building a railway in Africa benefit the individual African countries and the local economy? The answer, as Prof McCartney proposed, is to look at governmental policies. The impact from railways in Africa would be quite varied and the various African governments would need to work together to create a big picture for railway development in Africa. This is incredibly important, as highlighted by Prof McCartney, for railway systems are not built well by fragmented authorities. The African Union should draw lessons from the European Union as Europe has shown themselves more coordinated in the planning of railways. In short, for railways to success in continental Africa, it should be built in with a continental vision by a single authority.

The last lesson to be drawn from history in this seminar is the relationship between railways and institutions. Prof McCartney reminded the audience that railways is the first modern corporation in the world and it has transformed corporate life throughout history. However, Prof McCartney cautioned that with big developments, one needs to pay attention to instances of corruption, human right abuses, land speculation, amongst the other vices big projects and big money would bring. The concern would be, would big investments undermine institutions? Would the end justify the means? On the flip side, one could also ask if institutions would become better as a result of a thriving and prosperous economy?

Deep questions indeed for us to think about at the end of the seminar. Prof McCartney painted a very interesting picture on how infrastructure is a double-edge sword; would a better economy be the be all and end all? How do we balance the negatives with the positives? These are questions for another day and another seminar. We thank Prof McCartney for such an engaging and thought-provoking seminar during a time in which the world is looking at turbo-charging their own economies after a crushing pandemic. We look forward to learning more from Prof McCartney again.